Years ago, as a staff photographer for the Casper Star-Tribune in Wyoming, I had a photo assignment documenting a pair of biologists as they went searching for Townsend’s big-eared bats (Corynorhinus townsendii). We walked, stooped and crawled through a long-forgotten cave deep inside a mountain in Wyoming. I don’t remember the location, but I do recall we encountered and I photographed a few roosting bats. At one point in our descent, we rested against the cold, damp cave walls. We turned off our headlamps in unison and listened. It was the darkest and quietest place I have ever been. An otherworldly and awesome, place., and a perfect spot to record ultrasonic bat echolocation had I been thinking of sound back then, which I wasn’t. This was in the ’90s, and years before white-noise syndrome began ravaging hibernating bat populations throughout the country. A researcher today might think twice before having a photojournalist turned spelunker for the day tag along.

Ever since, whenever I see a bat at twilight, I don’t freak out and go after the tennis racket like I did when I was a little kid. Instead, I sit and watch them until the fading light makes it next to impossible to see my way home. This is where being able to record ultrasound saves the day. It extends it anyway, for my ears.

A quick and basic science lesson

Humans, if we’re fortunate to be born with the ability to hear correctly, can hear sounds from a little over 20 Hz to a little under 20,000 Hz (20kHz). With each passing year, our ability to hear those higher registers diminishes. Leaf blowers, hairdryers, and loud music from rock concerts we attend, steal an almost imperceptible amount that we don’t miss until we find ourselves turning up the volume on the TV. Most insectivorous species of bats, the kind we should embrace instead of swat at as they eat bugs that bite us during the day, are communicating, through echolocation, well beyond what we can hear. Their calls are between 20kHz and 60 kHz.

Eavesdropping on Bats

There are a couple of ways to tune into the bat conversation. The first is to buy a bat detector. There are cheap ones made from a kit and there are expensive, professional ones that scientists, like the bat biologists I hung out with, use. In the latter category, some detectors record in mono and a few that record in stereo. As a field recordist looking to capture a soundscape, only stereo versions appeal to me.

The second way to listen in on bats is the route I choose. Some microphones, and one particular recorder I use, can record up into the ultrasonic range. Most microphones max out around 20kHz. This is fine for most subjects but not, as we have seen, for bats. One bat eavesdropping contender is Sennheiser’s 8020 omnidirectional microphone. At $1,200 apiece, they’re not cheap. I’d want two for stereo. Instead, I have a Sony PCM D100 recorder (discontinued). It’s not cheap either but less than the Sennheiser above. Its two built-in swiveling microphones can capture sound above 20 kHz, although I don’t think there is documentation that says how high they go.

This past July, armed with my D100, a 10-foot light stand, a folding chair and a pair of binoculars, I sat up beneath the cupola of a barn near my home. I had begun seeing bats flying out of it while walking my dog at sunset. Maggie wanted to keep walking but she was overruled. We sat for a while.

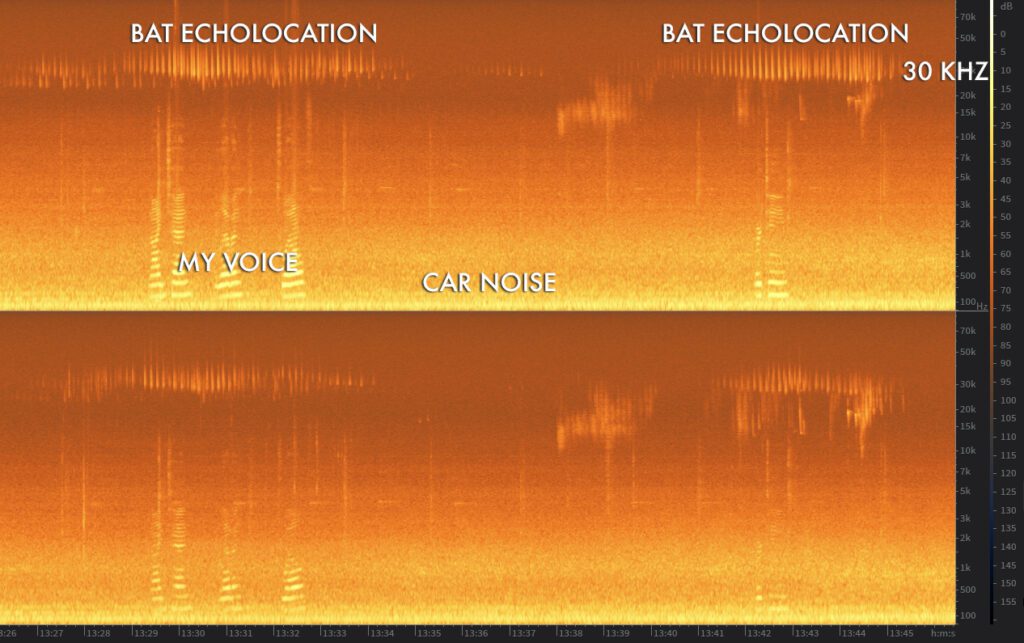

After recording, I needed a way to bring the 30 minutes and, 48-seconds of bat recording down to a human’s level of hearing. The way to do this is to record at the recorder’s highest sampling rate, 192 kHz. Then, back home, I used a low-pass ‘brick wall’ filter to notch out every frequency below 20 kHz. This eliminated all the road noise I picked up, along with my voice as I counted out loud the number of bats. I saw 87. Unfortunately, applying this harsh filter meant eliminating the few instances where I heard wings right over my head. Then, I pitch-shifted the recording down as low as the software permits (-36 semitones).

Now, when I playback the recording, I can ‘hear’ what the bats had to say as they left their roost. I imagine it was something like, “Hey, watch out for that guy sitting on that lawn chair! Yeah, what’s he doing? Doesn’t he know we have places to go and bugs to eat?”

Listen below to a time-compressed version of what I captured that evening. It’s in stereo, so use a nice pair of headphones. Bats exit the barn and fly past your right ear first.

See what bat calls looked like on my computer screen by viewing a spectrogram, a visual representation of sound, using Izotope RX Elements.

Further Reading

- Interested in knowing which microphones can reach up into the ultrasound? Field recordist Paul Virostek compiled an in-depth list of microphones commonly used for field recording, along with their specifications. View his fine work here. You’ll see that only a handful of mics foot the bill. That is why having the Sony PCM D100 is so nice.

- This page has a fantastic graphic depicting the audible ranges of different species, including us humans and bats.

- Interested in the variety of bat detectors available? Take a look at this bat detector buying guide.

- Here is a detailed PDF on Townsend’s Big-eared bat.

- Learn about white-nose syndrome, a fungal disease killing hibernating bats, first detected in New York state in 2006. Humans help spread the fungus when they enter caves wearing the same gear worn previously in caves where the fungus lives. More information can be found here at the White-Nose Syndrome Response Team.

Although his list doesn’t have specs for it, I found by happy accident that the Primo EM 172 omnidirectional mics (discontinued and replaced by the EM 272), sold by Fel Communications among others, record ultrasound. At least they captured bat calls when I was out recording above the Snake River in southwest Idaho this past April with my DIY binaural head.