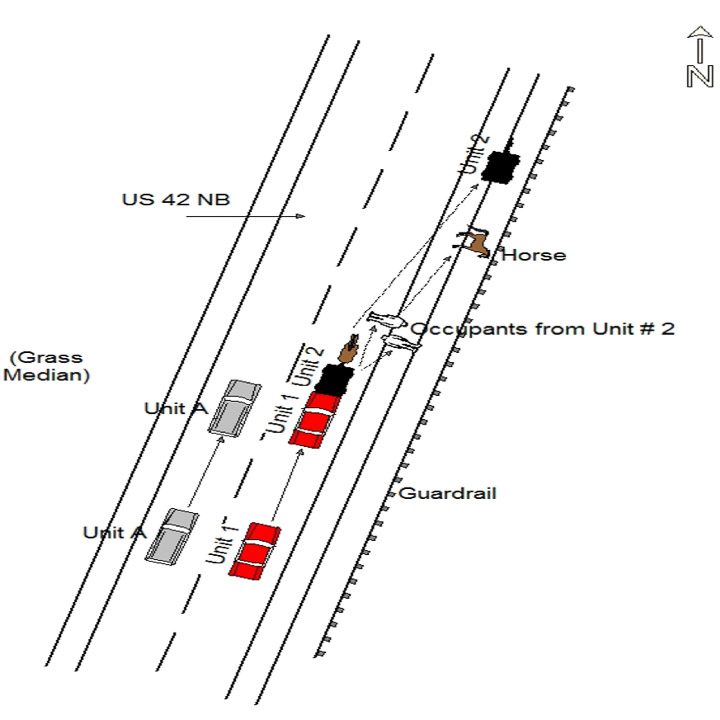

It was turning into a pleasant afternoon for early March in North Central Ohio. Although overcast skies triumphed over the sun to hold temperatures below freezing, the previous two days enjoyed highs in the low ’60s, keeping area roads dry. But for Anna Miller, driving with her daughter on a flat stretch of a divided four-lane highway on March 3, 2017, taking this road now would prove fatal. According to the Ohio State Highway Patrol, Warren Fletcher, of West Salem, Ohio, driving a red PT Cruiser with his daughter, slammed into the rear of Miller’s buggy. The collision sent the 48-year-old Amish woman from Polk, Ohio, and her daughter, Lovina, aged 21, flying through the air and onto U.S. 42’s asphalt. Lovina died at the scene along with the horse that drew the buggy. Anna died five days later.

What Time of Day Do Most Accidents Occur?

One might be under the impression that Amish buggy accidents involving automobiles happen mainly at night. After all, buggies are black, barely lit, travel too slowly, and are on roads too narrow for their own good. Statistics would, by and large, prove otherwise. The Ohio Department of Transportation (ODOT) has published detailed statewide Amish buggy crash data for the years 2007-2016. The takeaway from pages of colorful pie charts and bar graphs is that, in addition to 25 fatalities and 208 serious injuries during those years, 78 percent of all crashes occurred on dry roads, nearly two-thirds of all crashes occurred in daylight, and over half of all crashes occurred on straight, level roads. The most common crash scenario was a sideswipe pass. And more crashes occurred on a Friday than any other day of the week. All these factors are like what happened to Anna and Lovina Miller.

Interactive data compiled on the Young Center for Anabaptist and Pietist Studies website estimates that in 2018 there were nearly 325,000 Amish living in 31 states, the majority in Pennsylvania and Ohio. Amish live in three Canadian provinces and have recently called Argentina and Bolivia home. That’s four countries with growing horse-and-buggy communities. It’s safe to assume that motor vehicle versus buggy accidents occur nearly everywhere the two interact.

A quick internet search reveals years of headlines with references to children, adults, horses, and yes, even motor vehicle drivers, killed or seriously injured. A motorcyclist was killed on May 7, 2019, at 5 p.m. east of Cleveland after striking an Amish buggy and injuring its four occupants.

ODOT emphasizes that rural roads are not the same as city streets. Even the fastest horse is slow compared to a car. Also, an Amish buggy only weighs between 400-500 pounds. Comparatively, a Harley-Davidson Road Glide Special, one of the largest motorcycles on the road today, weighs more at 820 pounds.

To an outsider – an “English” as the Amish say – one might think horse-drawn buggies, the main mode of transportation that all Amish agree on using and a symbolic component of their culture and identity, are all the same. They are not. In general, the less conservative the Amish group, the more frills, including flashing LED caution lights and a slow-moving vehicle (SMV) triangle in the rear. The Swartzentruber Amish, being one of the more conservative subgroups of Old Order Amish known for its resistance to change, refuse to use the SMV symbol, considering it too flashy.

Some group members in Kentucky were jailed instead of submitting to what they said violated their simple religious belief of avoiding “worldly symbols.” Black is by far the most common shade of paint seen on Amish buggies, but not the only one. The Byler Amish of Mifflin County, Pennsylvania has yellow-topped buggies. The Nebraska Amish, also of Mifflin County, drive white-topped buggies. Brown and gray-topped buggies can be seen in Amish communities in Pennsylvania and in New York. Requiring all Amish to drive flashy buggies may seem like the perfect solution for something that is nearly invisible at night. Yet we do not require every vehicle on the road to be this bright and bold.

While they may not agree upon a universal hue for their buggies, one thing most Amish can agree on is that there are more vehicles on the road than in the past. Motor vehicle drivers face more distractions than ever before, with talking and texting on cell phones being the prime offender. Amish, traveling at a much slower pace than automobile traffic, have more time to observe these behaviors as fast-moving vehicles come within inches of their horses and buggy spokes.

Why all the graphic detail when this is a story about recording sounds of the Amish?

I grew up on the edge of Ohio’s Amish country. As a child, I would stare at Amish walking the aisles of my hometown hardware store. I watched as they drove their buggies through our one-stoplight town square. The novelty of those sightings turned to teenage annoyance when I learned to drive, invariably getting behind an Amish buggy on a hilly Ohio road. If you’ve ever been stuck behind a farm tractor along a rural road, you know how frustrating this can be. I left Ohio and the Amish behind on my 30th birthday, moving out west and then to the Deep South before finally moving back home in 2015. By then I was older and wiser and interested in capturing soundscapes lost to most of us. The Amish community seemed like the perfect avenue to discover these sounds if only I could gain access to their culture.

The first newspaper I worked for published an Amish tabloid with, it seemed, variations of the same stories done in previous years, and a lot of advertising. Amish shun the camera, but I had to come back with something to help fill the pages. I found myself hiding beside buildings and shooting from car windows, ambushing Amish children and clip-clopping buggies up and down the streets of Sugarcreek, Berlin and Millersburg. My sister has one of these photos on her wall. Every time I look at it I am reminded of my brief paparazzi past.

I learned to work the edges of a story first. Not to barge right in. My inroad into the Amish community was to record the sound of a windmill. Nothing too intrusive there I figured. Almost every Amish farm around has one. I hoped that capturing its repetitive up-and-down thumping sound under a slight breeze would make an interesting recording. With this in mind, I drove north, spotted a metal windmill and approached the unassuming head of the household. Ivan Miller was polite but clearly confused by my request to record. But to my surprise, he allowed me to hook up my microphones.

Through Miller, I met Milo Yoder, his Amish neighbor down the road that, along with farm chores, makes handmade leather fly swatters in an outbuilding adorned with abandoned hornet nests. His dirt-floored leather shop houses an assortment of heavy, diesel-powered industrial sewing machines and other contraptions to get the job done. One afternoon inside this “man cave,” his words not mine, we discussed our favorite Johnny Cash songs. My favorites are from his Nine Inch Nail and U2 covers. His are from Cash’s more religious songbook. I broke out a couple of harmonicas. Both of us could have used a few lessons.

While the Amish avoid photography, everyone I met was very open to my microphones, to the point of suggesting sounds I should definitely record. The sound of cow’s milk pouring into a stainless steel container is one example. They hear this up close twice a day.

Perhaps it was the newness of hearing their own voices and surroundings for the first time on tape, or something else, but my requests to record were denied only once, and that was when I stumbled upon an Amish wedding held inside a large farmhouse. Its downstairs windows were wide open, and I could hear every drawn-out syllable of their slow-paced hymns from the road. Outside with the father of the bride, I pleaded my case to record. He turned me away in a polite manner that I began to realize was so Amish. Oh, if I could have had a microphone in the middle of that living room.

Each Amish settlement has rules that govern how they interact with the “English.” Like most Amish I met, Milo is able to use a telephone but does not own one. So I would show up unannounced. He allowed me to record the sound of distant, rumbling thunderstorms from inside their old wooden red barn as a steady rain pelted its metal roof. I watched as his daughters milked cows under kerosene lamps during early-morning chores. I was invited inside his home to hear the collective sounds of his prized grandfather clocks. I followed behind as he and his boys gathered up crops for the winter. I couldn’t thank him enough. During the August 2017 solar eclipse, I made shoebox viewers for his children to look through. We spread out across his front lawn to watch the show. It was the least I could do.

I handed over headphones to the children gathered around my recorders, trying to instill in them that growing up in the country, and hearing sounds that have faded from modern American life, are gifts to be appreciated and valued. This one thing – sharing the experience – is what most likely allowed me to gain access.

What Can Be Heard on the Album?

On “Sounds from a Simple Life, The Amish in North Central Ohio,” in addition to the sounds mentioned above, you’ll hear the sound of plain-colored Amish clothing hung out to dry in a stiff breeze at Johnny Raber’s farm. With notoriously large families, Amish laundry lines are quite long. His pulley system clothesline, at 200 feet, is no exception.

Cornfields are everywhere in Ohio’s Amish country. I got down and dirty several times to record cornstalks crackling in the wind. The best take came when the corn was driest before the stalks were shocked in December.

You’ll hear an Amish windmill pumping cold water out of the ground below while chickens roam around a barn. It can be a hypnotic, sleep-inducing sound.

One cold February morning, I was granted permission by a young teacher, who like her pupils, only attended school through the eighth grade, to record the opening moments of the day. Outside the white, one-room cinder-block schoolhouse, boys kicked a soccer ball before class in front of my microphones. Most of the girls stayed inside and gathered around their teacher’s desk. As the teacher pulled the rope to ring the old cast iron bell atop the building, the boys came running. Each one said “good morning” as they filed across the creaky wooden floor and into their seats. The students then opened their wooden desks and settled down for lessons.

These were all special moments, yet the sound I wanted to capture most eluded me. With every request to record one chore or another, I would ask to record a buggy ride. I captured plenty of buggies passing by. That wasn’t good enough. I wanted to ride along. To experience what it feels and sounds like when a truck goes speeding past a slow-moving buggy and horse at 60 mph.

My persistence finally paid off when I met Daniel Weaver, age 17 at the time. Daniel had recently started a sawmill business he operates with his father Elmer. Unlike “English” teenagers that are learning to drive at his age, Weaver is a veteran, handling horse-drawn buggies on Ohio’s back roads since his early teens. Along with his younger brother, Weaver allowed me to catch a ride as they drove a mere six and one-half miles to a job site where young Amish men wrangled chickens destined for a slaughterhouse in Pennsylvania. The jarring trip took over 40 minutes one cold, wet January morning.

There are no mirrors on Amish buggies, at least none that I saw. And unlike those driven by nearby Mennonites, Amish buggies around north central Ohio don’t use rubber-rimmed wheels. The 16-spoke steel wheels thus create a low, grumbling sound and generate a fair amount of shake as they roll over asphalt and gravel roads. All this makes it next to impossible to hear, let alone see vehicles approaching from behind. And from behind is how most Amish buggies are struck. While I was ecstatic to finally be recording what I set out to do, I was scared to death at the same time.

Well, I just don’t know if I’ll get home at night. It’s a different feeling if you’re on that big road.

– Milo Yoder

Milo Yoder has been in two buggies versus automobile accidents in his 54 years. Plus he’s had a few close calls. With milk prices down, he took up a part-time job at a nearby shed fabrication company. He told me that he says a prayer every morning as he turns into busy semi-traffic along Ohio Route 13, a humming two-lane highway that crisscrosses the state. “Well, I just don’t know if I’ll get home at night. It’s a different feeling if you’re on that big road.” When asked if Amish should be required to drive on roads built exclusively for them, Yoder says, “A lot of people think we don’t pay taxes well we do that, but I don’t think we should have our own roads because we’re in America. It’s not your road and it’s not my road, but it’s our road.”

Milo’s relative Rosie Yoder, 58, runs a little general store catering to the Amish in her community. She has seen her share of family tragedies. At age 6, she rushed to see her mother’s body, electrocuted while picking apples. An aluminum ladder was placed too close to a low-hanging power line. “She was burned so hard there was holes burned in the shoes she was wearing,” Yoder said. At age 18, she learned her brother had died after a tree fell on him. And at age 13, a drunk driver hit the buggy she was riding in, leaving her wheelchair-bound with a spinal cord injury, her brother with brain damage, and her sister dead.

Listen as Rosie Yoder tells her story below in a February 2018 interview.

My hope for this album is that after listening, your appreciation and understanding of the Amish going about their lives, on the roads, and in the fields, will grow. Take a moment to contemplate the disappearing sounds so few of us have the pleasure of hearing in the world today. Finally, for everyone’s benefit, consider slowing down when you come across a buggy while driving through Amish country. Pullover even, purchase a dozen eggs and listen to a windmill. You never know where it will lead.

Update July 5, 2019:

Today I was informed by Joe Lyons, editor of Ashland County Pictures on Facebook, of yet another Amish buggy versus vehicle accident that occurred July 2, this time involving a 7-month-old Amish child that along with the horse, amazingly came away from the accident unscathed. The other two buggy occupants did not fare as well as all three were thrown from the wreckage. This latest wreck occurred on the same stretch of roadway as Miller’s accident, which led off this story.

In September 2000, ODOT released an analysis and action plan entitled Amish Buggy Safety on Ohio’s State Roadway System. Although the study is nearly 19 years old, the attitudes and proposals listed in it are still hotly debated and seldom implemented. One bullet point that stands out to me is a realization of the need for better education, for both car and buggy drivers. But read some of the comments under Joe’s moving photographs from the accident scene. You’ll see that the number of ‘English’ drivers opposed to Amish sharing ‘their’ roads far outweigh the commenters offering prayers. I find this sad on so many levels. The responsibility is on us, the drivers of 4,000-pound pickup trucks and SUVs, to be diligent on the roads, and to quit switching the blame and responsibility onto the Amish.

Want to learn more about the Amish? Check out these websites:

- Amish Studies is an academic website developed by the Young Center for Anabaptist and Pietist Studies at Elizabethtown College.

- The Holmes County Chamber of Commerce and Tourism Bureau would like you to stop by.

- Mission to Amish People is an organization founded by Amish who have left the fold. That said, they keep a detailed record of Amish buggy vs. vehicle accidents.

- Amish America, is a site hosted by a non-Amish from North Carolina. Nevertheless, he presents a lot of interesting information. And his logo features a windmill, which I like.

- amish365.com showcases many good baking and canning recipes. Yum.

- The Missouri Folklife Society has a plain but well-informed page on Amish in their state.

- PBS, with its ongoing series American Experience, produced a fantastically researched series on the Amish.

- And then there’s Wikipedia’s definition.