Say you are walking in the woods past a hollow in a tree. Have you ever stuck your head inside to hear what it sounds like? I have, several times. Even if there were a parade of hikers, I’d still do it.

I love trekking through woods and along tree-lined paths on windy days. Every so often if the wind is right, I’m rewarded with a creaking sound of a dead tree, a snag, in forest ecology terms, rubbing against its more-fortunate neighbor. As a nature sound recordist, I search these snags out, standing motionless upon the first hint of hearing them. My ears perk up, anticipating the next wind gust that drives the desired sound.

I use a pair of contact microphones, space them as far apart as I can reach, then clip them onto 10-penny nails I hammer into the snag’s trunk. This way, I’m able to extract deep, hidden, resonant sounds unheard by the naked ear. With every forlorn moan and groan, snags tell a one-of-a-kind story based on their size, location and the amount of wind that torments them.

This recording series has not been without setbacks. For example, a large cottonwood snag currently resides in the middle of the Boise River near my home. I’ve been eyeing it since last spring’s high water brought it there to rest atop man-made rapids. Recently, I put on tight rubber boots and hopped from rock to slippery rock to this lonely snag. I straddled the tree, attached microphones and pressed record. Nothing but monotonous white noise, unworthy of recording. It was worth a try.

At other times I’ve had better results. I recorded a healthy Live Oak tree scraping against a large, crumbling 19th-century family tomb in the middle of Baton Rouge’s historic Magnolia Cemetery. Winds blew out of the north at 8 mph, enough to make the Spanish moss-covered giant sway. The tomb, most likely hollow, as a South Louisiana summer would have turned it into a slow cooker ages ago, became a gigantic upright bass. The outstretched tree limb became its bow, composing a haunting lament.

In 2012, limbs from the sprawling tree had not yet reached the tomb. During my 2015 visit, a fist-size limb had grown long enough to gnaw at it. During a follow-up visit a few weeks later, I found the tree cut back. Curses! For a short time, this live oak planted perhaps during the cemetery’s inception disturbed the eternal peace for these poor souls. Mother Nature’s dirge.

If you’re a tombstone tourist like me, curious about whose remains reside in the tomb, you’re out of luck. I checked with Sexton Chip Landry, who replied many grave records, including this one, went up in a fire at a former sexton’s house in the 1930s.

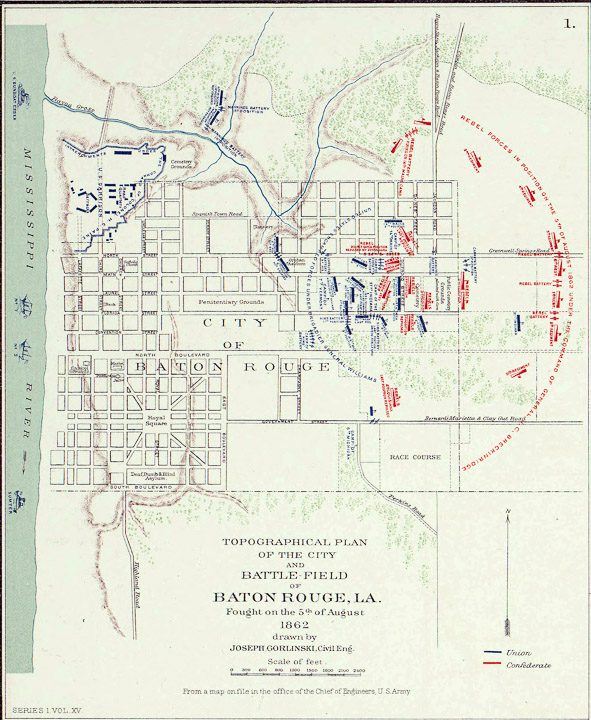

As a side note, on August 5, 1862, Magnolia Cemetery became the center of fierce fighting during the Battle of Baton Rouge. Who knows, soldiers may have hidden behind or perished beside this tomb.

I trekked along boardwalks in Fowler Woods, an old-growth forest in north-central Ohio featuring American beech and maple up to 300 years old; plus Pumpkin ash and a few other species thrown in. Trees in swampy sections of the preserve avoided the ax. Yet ash trees could not escape the Emerald Ash Borer, a shiny greenish-colored invasive beetle brought over from China. It’s the larval stage of the bug that wreaks havoc, leaving Fowler Woods looking like a giant game of pick-up sticks. Exactly the kind of recording environment I was after, as 18 mph wind gusts blew in from the northwest.