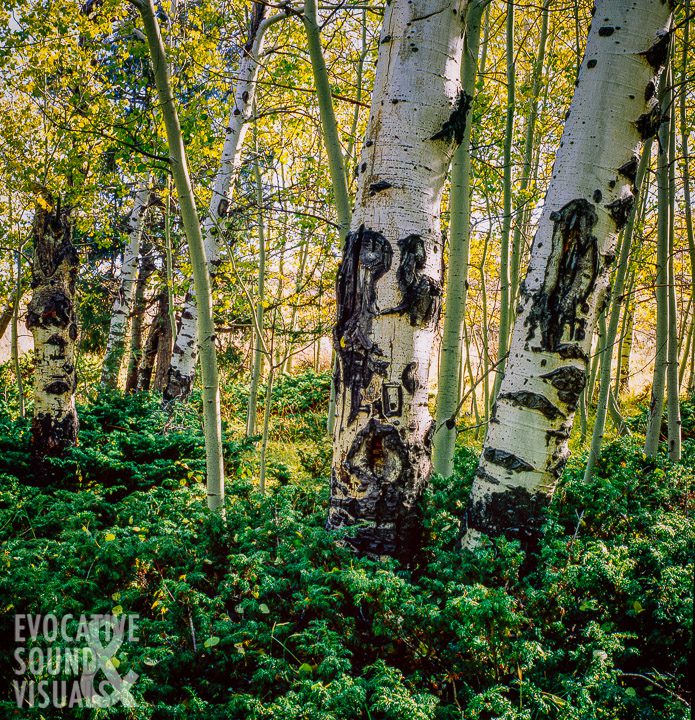

Listening to the wind blowing through the trees is one of life’s simple pleasures. There is no better time to lay down and relax beneath the branches than in the fall when deciduous trees trade their greenery for vibrant displays of yellow, red and orange. Here in the Rocky Mountain West, the Quaking Aspen puts on the show. The unique sound their leaves make before falling to the earth is not to be missed.

Not only is this landscape makeover a feast for the eyes; it’s a treat for the ears. Like any leaf, the drier aspen leaves become, the crispier the sound they produce when they touch. A flat aspen stem connects at an angle to the leaf, unlike other deciduous trees with a round stem that joins their leaf on a straight plane. This perpendicular configuration gives aspens their unique “quaking” sound. Their scientific name, Populous tremuloides, is spot on.

Aspens claim bragging rights for spanning the widest natural range of any tree in North America, from Alaska to Mexico. These trees have evolved to grow at lower altitudes in the north, and higher altitudes the farther south they go, between 5,000 and 12,000 feet in elevation.

They also lay claim to being the biggest and heaviest organism in the world. Although they can propagate by seed, by and large, aspens reproduce asexually, in stands called clones. One clone colony can be distinguished from another, as the leaves on every tree in that clone will change color at the same time.

The largest clone – consisting of over 40,000 individual trees – has a name. It’s called “Pando,” located in central Utah. The colony, spreading over 106 acres and weighing 13 million pounds, began toward the end of the last ice age, according to the U.S. Forest Service. One giant root ball to be sure.

While it may seem as if the species is doing fine here in the Rocky Mountain West, such is not the case. It has a name as well: Sudden Aspen Decline (SAD). It is a cute acronym for a truly sad phenomenon. There are explanations. For starters, aspens are not a shade-tolerant species. Something inside them wants to show off those bold colors. Fire suppression here in the West is allowing taller trees to thrive and block the direct sunlight aspens crave.

Drought and climate change also play a negative role. At Pando in particular, bark beetles and root rot are stressing out the overstory, while increased deer and other sharp-antlered ungulates are distressing the lower half, according to the U.S. Forest Service.

Individual aspen trees can live to be 150 years old on average. When immature trees cannot gain a foothold, scientists monitoring the lack of regeneration are put on alert. Their worst fears for Pando are a sizable or complete die-off of the clone.

For me, it is vital to hear the sound these trees make before they are gone. Around this time last year, I took a few trips to the Long and Wood River valleys here in Idaho, seeking shade and quiet beneath the trembling trees. Much like an elk, a deer or a moose would during hot Idaho summers.

I began recording north of Long Valley, where the gentle wind flowing through the aspen leaves made for a soft, whispering bed of sound that contrasted with the loud repeated “shook, shook, shook, shook, shook” of a Stellar’s jay. I then headed south, to a quiet spot nestled among the braided channels of the North Fork of the Payette River, elevation 48,00 feet. Lastly, I sat for hours on rotting logs beneath mature stands in the Wood River Valley northwest of Ketchum and near Deer Creek east of Hailey, blissfully taking it all in. Winds intensified all around me, kicking up the still magnificent smell of dried, spent sagebrush and unspoiled earth. The trees rocked back and forth, their leaves twisting like tinsel on a Christmas tree. I was at peace.

The sound clip below is from the middle of a 35:59 compressed recording, featuring three different locations captured at the end of September and the beginning of October 2018. I used a Sound Devices 702 recorder (96kHz/24-bit) and Audio Technica 3032 low-noise omnidirectional microphones in an A/B configuration. Purchasing the album gives you access to the entire recording described above.

- Learn more about the Pando colony here and here.

- Learn more about Aspen ecology at the U.S. Forest Service site here.

- Now a bit dated, this paper from the Forest Service discusses SAD in more detail.

- The Arbor Day Foundation wrote about aspens here, as did the National Wildlife Federation here.

- View an interactive ArcGIS map showcasing the current range of aspens in North America here.

- Read about the mystical, magical and medicinal properties of the aspen tree here, at The Goddess Tree website.